The Rights of Nature: A call for a policy of mutually assured flourishing

Alban Krashi, Gina Moran, Amy Carter-Gordon, Mel Lacey, James Lock and David Cotterrell

Link to full paper - People Place and Policy

Abstract

The new Labour government faces numerous, interconnected crises along economic, social and environmental nexuses. Policies intended to address issues such as the cost-of-living, healthcare and housing crises are receiving particular attention. Parties have presented narratives around the ecological crisis, such as a significant expansion of renewable energy and reduction of carbon emissions; these are vital, necessary starting points. However, the current discourse is shallow and fails to grapple with the root causes of an operating system that is ultimately self-terminating. We contend that a truly sustainable and regenerative social-ecological transformation must transcend the status quo and fundamentally shift our ontology (ways of being and relating).

In this article, we explore and advocate for a Rights of Nature (RoN) policy. This would not only involve innovative legal and governance mechanisms to ascribe legal agency to more-than-human actants and incorporate them into infrastructures; it would also support the transition of ontological shifts towards relationships of interdependence and stewardship with the more-than-human world. Here, we review the literature on the Rights of Nature, especially highlighting the River Dôn Project (RDP) as a key case study. We explore the necessity of transdisciplinary collaboration and thinking and explore how the UK could demonstrate alternative RoN realities. We conclude by arguing that projects such as the RDP and broader Rights of Nature must be a critical focus of the new Labour government, to ensure our mutually assured flourishing with nature, rather than our mutually assured destruction.

Introduction

The new Labour government faces a multitude of national and global crises, interconnected along economic, social and environmental nexuses. These include sewage pollution in rivers and waterways (Stuart-Leach, 2023), the rising cost of living (de Hoog et al., 2022), a failing healthcare service (Triggle, 2023) and more frequent and severe climate change-induced weather extremes (Hanlon et al., 2021). The government has announced and started to enact policies that are necessary starting points to address the environmental crises, such as lifting the onshore wind ban and pledging no new oil and gas licences, though the latter already faces contention (Loughran, 2024; Ambrose, 2024).

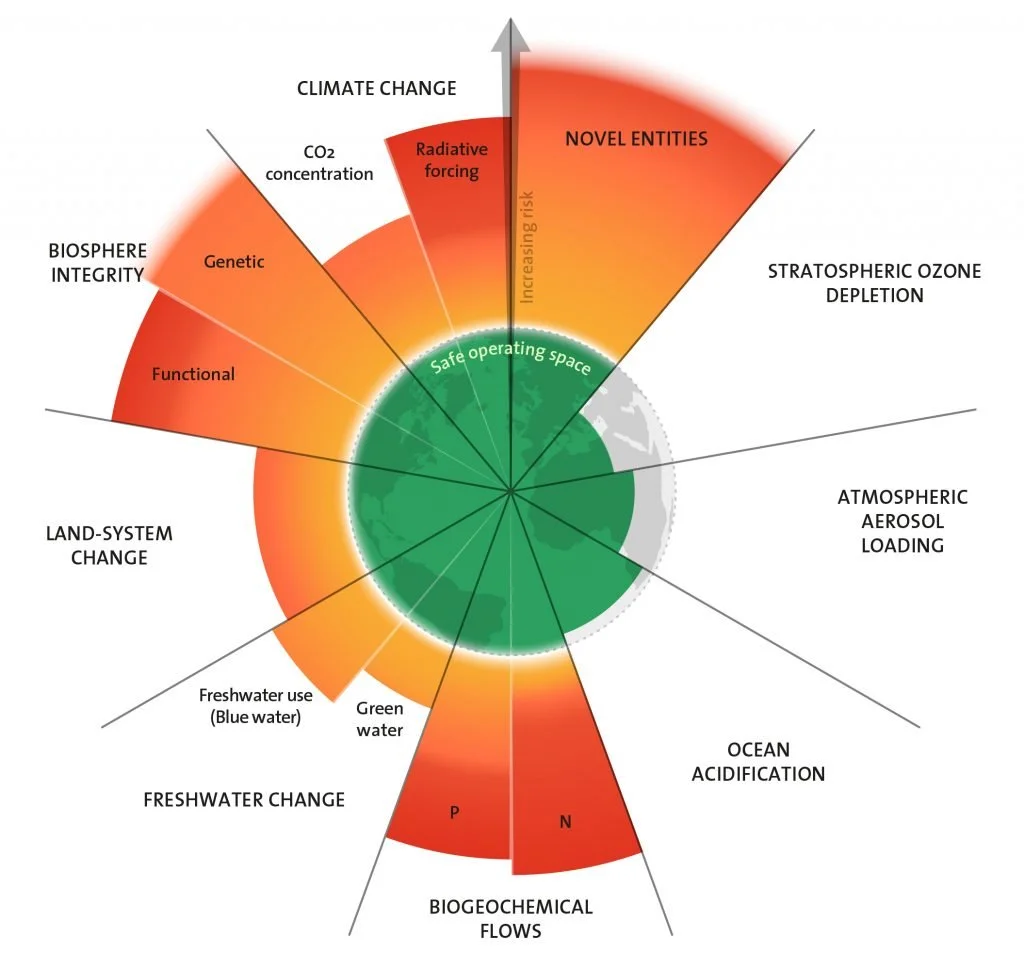

Sadly, these policies fall short in the face of the rapid ecological and social breakdown in the UK and internationally. We are failing to meet many of the basic social foundations conducive to a good life, such as equality, sanitation and energy access (Fanning et al., 2022; Raworth, 2017a; 2017b). Concurrently, at a planetary scale, our economies and societies are surpassing the carbon emissions, nitrogen and phosphorus pollution, and ecological and material footprint required to stay within planetary boundaries (Figure 1) (Richardson et al., 2023).

Figure 1: (Exceeded) planetary boundaries

Credit: Azote for Stockholm Resilience Centre (2023), based on analysis in Richardson et al., 2023. Attribution: CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.

Ecological economists have long argued that these interconnected failings are highly related to our growth-centric and extraction-based economic model, which positions the environment as an infinite resource to be infinitely extracted from, rather than the finite, exhaustible system we live within (Daly & Farley, 2011; Dietz & O’Neill, 2013; Raworth, 2017a). It is necessary to move to a different kind of economy, informed by a different way of being and a different future (Dietz & O’Neill, 2013; D’Alisa et al., 2015), such as Kate Raworth’s doughnut economics theory (Figure 2) (Raworth, 2017b). We argue that the sustainable social-ecological transformation necessary to safeguard human and more-than-human life on this planet must transcend the extractive, growth-centric status quo and fundamentally shift our ontology.

CLICK HERE to read the full paper